In the chilly air of Ontario stands an old, forgotten provincial prison, gradually falling apart with time. Burwash Correctional Center, built in 1914, used to be a bustling place. Inmates built a whole community here to house about 1,000 residents who worked in the prison and on its farm.

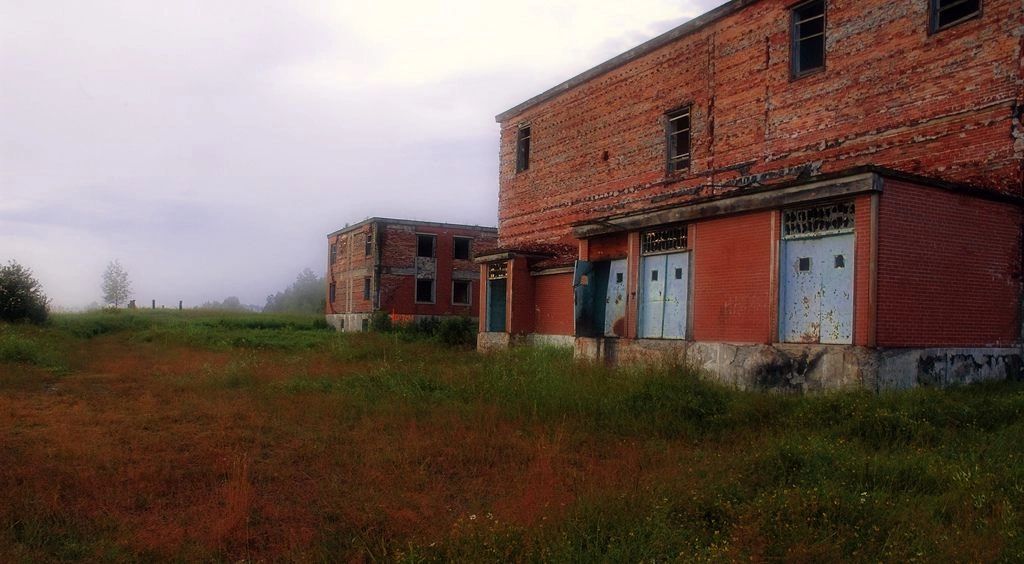

But over the years, the cost of keeping the facility running became too high. In 1975, Burwash Correctional Center had to shut down, leaving its distinctive red brick buildings to face the elements alone. Despite being abandoned, the site still draws a few adventurous people eager to explore its crumbling halls and lost history.

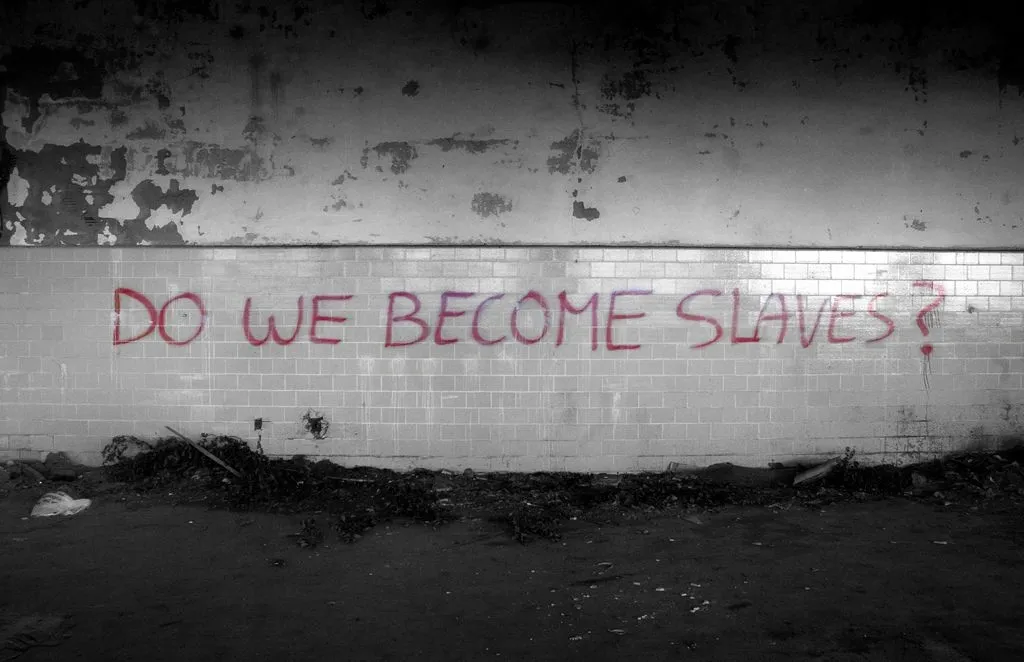

Today, the once lively Burwash Correctional Center lies in ruins. The walls are covered in peeling paint and graffiti, broken glass is scattered across the floor, and weeds are growing through the cracks. Moss, rust, and an eerie silence have taken over the abandoned prison, which is slowly decaying in the cold Ontario air.

At its peak, Burwash housed between 180 and 820 inmates. Originally remote, the prison became more accessible with the construction of Highway 69, leading to a community of prison workers and support staff around the facility. The inmates helped build this community, constructing a church, a post office, a tailor shop, and a shoe repair shop. One inmate even ran the local barbershop, sometimes shaving the very guards who watched over him with a straight razor.

Inmates at Burwash Correctional Center played a big role in keeping their community running. They grew fresh meat, fruit, and vegetables on the prison farm, baked bread to sell at the local grocery store, and cut down trees for the nearby sawmill, using the wood to build structures. Burwash became almost self-sufficient, offering inmates the chance to get an education, learn trades, and feel a sense of belonging despite the constraints of prison life.

The prison housed only low-risk inmates serving up to two years. In a 2013 interview with The Sudbury Star, former corrections officer Dave Webb, who worked at Burwash from 1957 until it closed, described it as a fair place: “Nobody was abused. If an inmate wanted to do good time, he had a good time. If he wanted to make it difficult for the staff, it would be difficult.”

However, not everyone saw Burwash in a positive light. Some inmates considered it “a hellhole.” David Clayton-Thomas, a notable former inmate who later became the lead vocalist of Blood, Sweat & Tears, described his experience in his 2010 autobiography: “This was no summer camp… All conversation is forbidden, and any attempt to communicate is punished by a high-pressure hose poked through the door slot and unleashed on the prisoner.”

In July 1974, Ontario’s Minister of Correctional Services, Richard T. Potter, announced the closure of Burwash Correctional Center. Despite differing opinions from guards, residents, and inmates, the facility was considered too expensive to run, and closing it was seen as a cost-saving measure for the provincial government.

By 1975, the town’s roughly one thousand residents, living in 175 houses, were told they had to leave. The inmates were relocated, and Ontario started looking into new uses for the prison complex and its 35,000 acres of land.

Eventually, the Federal Government purchased the property for $1.8 million. Part of the land was leased to the Regional Municipality of Sudbury for an angora goat farming project, which ended up being a financial failure. In the 1980s, the land was sold off to various entities. The Department of National Defense acquired a significant portion for military training, while other sections went to the Ministry of Natural Resources and the Ministry of Transportation, which used some of the gravel reserves for road construction projects.

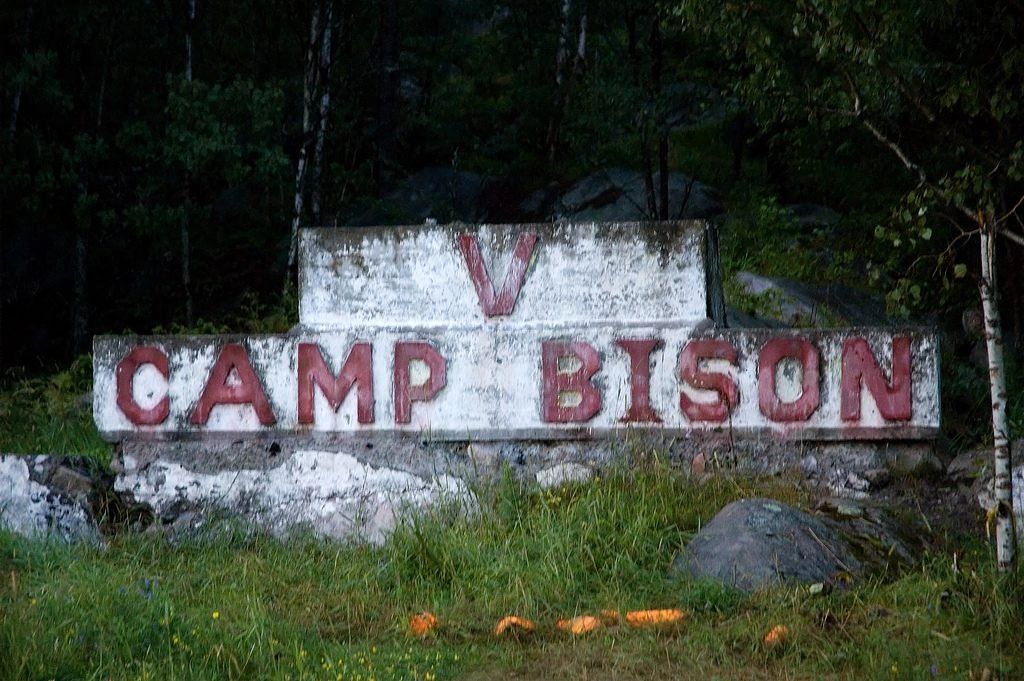

By the mid-1990s, nearly all the buildings at Burwash Correctional Center had been demolished. Only the main prison complex, known as Camp Bison, and the prison cemetery remained. The cemetery is the final resting place for an estimated 12 to 20 prisoners who had no family to bury them elsewhere.

On August 6, 2006, the Ontario Heritage Trust acknowledged Burwash’s historical significance by unveiling a commemorative plaque at the site. About a year later, the cemetery was cleaned up, and a signpost was put up to mark its location, preserving the memory of those who lived and died at Burwash.