The Dunnington Mansion, also affectionately known as Poplar Hill, graces the landscape of Farmville, Virginia. No, it’s not just a reference to the digital realms of Facebook; it’s a real gem nestled in the heart of Prince Edward County, which was once known as Amelia County until February 27, 1752.

This historic residence commands a view over the undulating terrain of the Manor Golf Club – a picturesque golf course boasting meticulously tended fairways and weekday greens fees as reasonable as $33. And no, I’m not trying to sell you on it. I should really start packing my clubs more often; you never know when you might stumble upon an abandoned mansion smack dab in the middle of a golf course

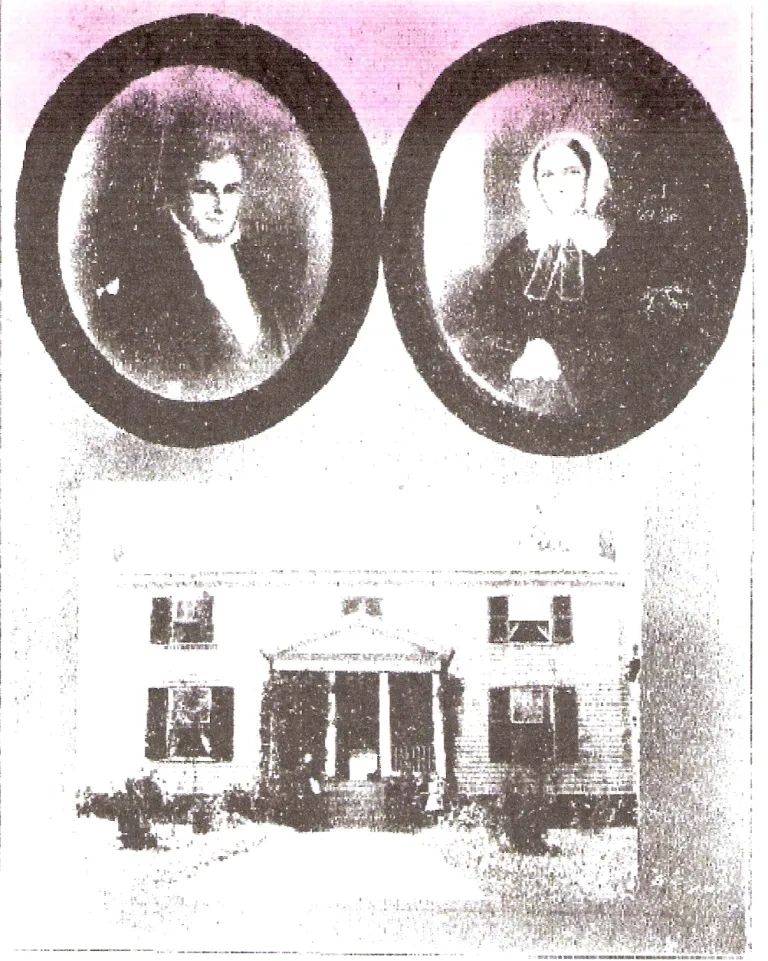

The Dunnington Mansion, a composite of various additions dating from the late 1800s to the early 1900s, has roots that stretch back to the 1700s when Richard Woodson, also known as Baron Woodson, acquired the land in Prince Edward County. Born in 1695 in Henrico County, Virginia Colony, Woodson established the Poplar Hill Plantation, erecting the initial version of the residence, a modest four-room dwelling.

Following Woodson’s passing in Goochland County, Virginia, in 1774, the estate passed to his daughter Agnes, born on October 4, 1748. Agnes and her husband, Francis Watkins, replaced the original structure with a sturdier brick house toward the end of the 18th century. Concurrently, other buildings, including quarters for enslaved African-Americans, were erected on the plantation, as evidenced by historical atlas maps, although these structures were eventually razed between 2004 and 2006.

Agnes died in July 1820 at the Poplar Hill plantation, with her husband following six years later in 1826. Their daughter Frances inherited the property, one of six children, and resided there with her husband James Wood.

The mansion, now referred to as the Wood Plantation house, underwent further expansion under the ownership of the Wood family. After about four decades of their stewardship, the property changed hands once more, this time falling into the possession of Captain John Hughes Knight Junior. Knight, son of Colonel John Hughes Knight and Sarah “Sally” Everett Carter, exchanged vows with Cornelia Alice Bland on October 12, 1853, at Richmond, Virginia’s First Baptist Church, still an active congregation today. Shortly after their marriage, they acquired the Poplar Hill property, where they resided until the late 1880s.

Upon Knight’s passing, the estate passed to his daughter, India Wycliffe Knight, and her husband, Walter Grey Dunnington, a prominent figure in the tobacco industry. This marked a significant juncture in the mansion’s history, as it was poised to undergo its most extensive reconstruction yet.

In 1897, Dunnington embarked on an ambitious project to essentially reconstruct the entire home around its existing smaller structure. Following the renovation, the home’s footprint expanded to a generous 8,500 square feet, now boasting a total of 14 rooms. The foyer alone was a monumental undertaking, commanding considerable expense. Intricate woodwork adorned the grand staircase, complemented by an exquisitely crafted brick fireplace near the entrance. The exterior of the house was fashioned in the Romanesque Revival style, while inside, a blend of Italianate and Victorian architectural elements adorned the interior.

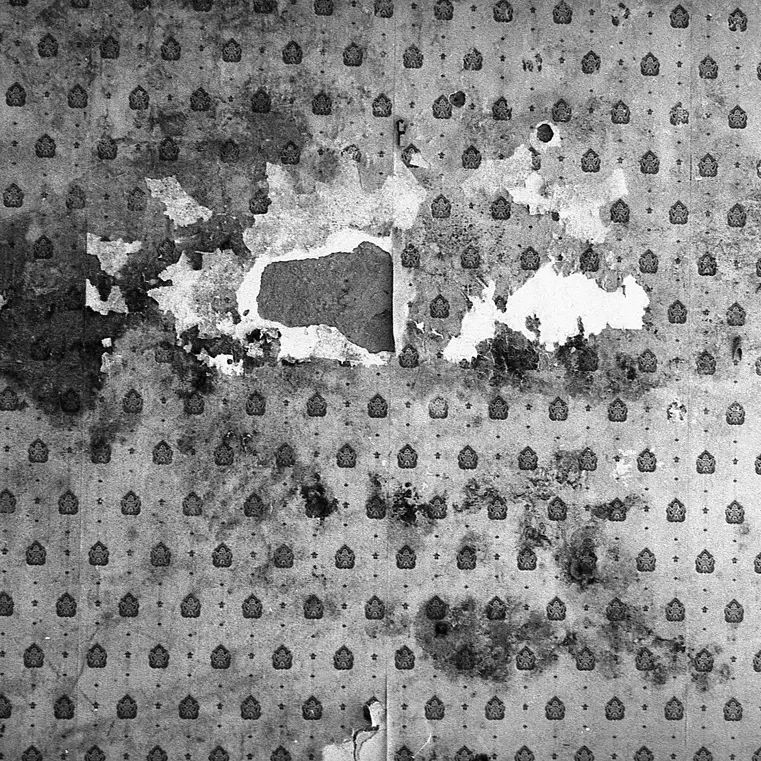

Upon stepping into the home, a doorway to the left revealed the remnants of the once-opulent study. Years of neglect had taken their toll; the floor had succumbed to decay, making navigation precarious. Ceilings lay in disarray, and only the fireplace and some dilapidated bookshelves remained, bearing witness to the room’s former grandeur. Continuing through the study, the formal dining room emerged, its walls now peeling with neglect. Here, the Dunnington family had once played host to numerous gatherings, entertaining affluent guests amidst the opulent ambiance. The dining room windows, once sources of natural light, now stood obscured by cobwebs and a thick residue, diffusing the sunlight that filtered through, casting a ghostly pall over the space.

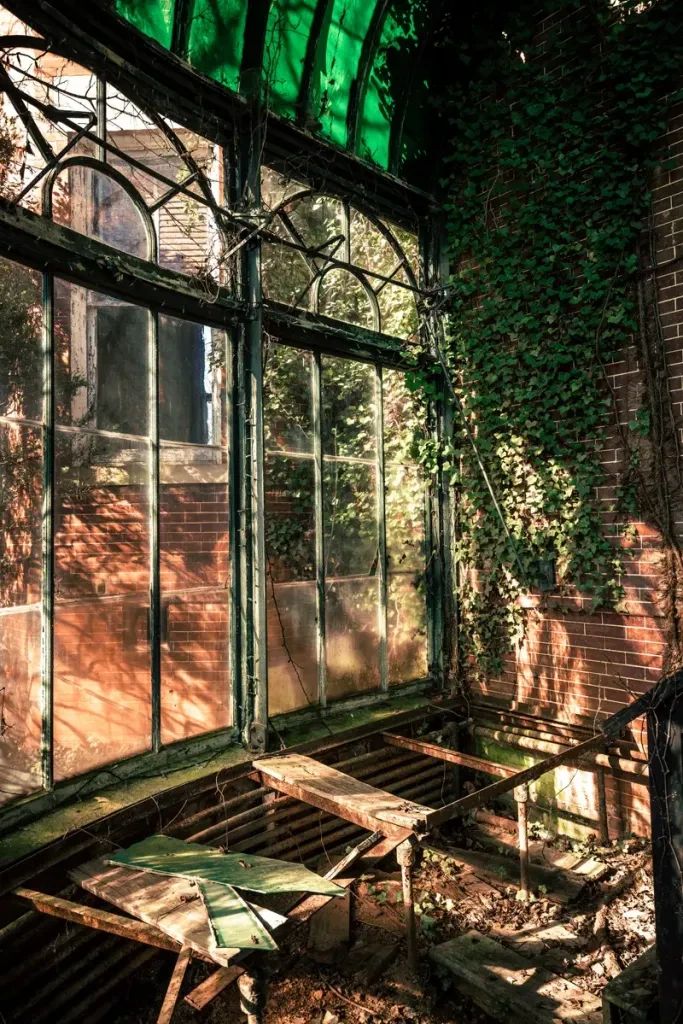

On the opposite side of the hallway from these two rooms, two adjoining parlors now lay in disrepair. One opened onto the porch, while the other revealed a remarkable space—one of the mansion’s most striking architectural features. The Italianate-style domed glass conservatory, though weathered and crumbling, retained a serene beauty both inside and out. Breezes gently stirred the ivy, swaying amidst the cracked panes, creating a tranquil atmosphere filled with the soft melodies of birdsong and the earthy scent of nature reclaiming its domain.

Upstairs, intricately detailed archways connected corridors and staircases, while Victorian fireplaces adorned many of the rooms. Turret alcoves provided cozy retreats, basking in the warm glow of the November sun filtering through their windows. These nooks, once perfect for leisurely sun-soaked moments, now exuded a sense of timeless charm. As for the staircases, they seemed to multiply, reminiscent of an M. C. Escher artwork, perhaps originally designed to segregate servants from the family or guests, a practice happily relegated to history.

At the pinnacle of the home lay a spacious attic, its original brown wood now softened to a serene off-white hue by the presence of countless avian residents. Ascending the stairs, I discovered yet another door leading to a balcony nestled within the graceful arches of the home’s facade, facing the northwest. One can only imagine the countless evenings spent here, basking in the glow of the setting sun.

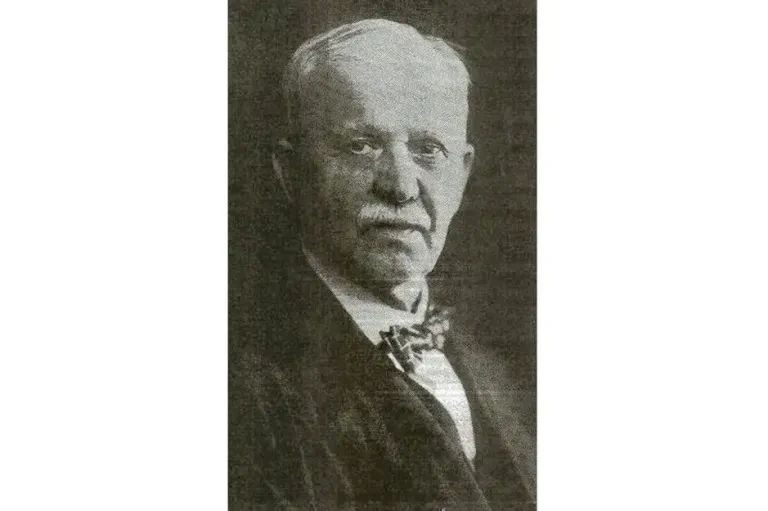

Walter Dunnington’s opulent lifestyle at the Poplar Hill mansion hints at his substantial wealth, but how did he amass such a fortune? Well, let’s delve into his backstory.

In 1870, Walter’s father, James W. Dunnington, established the Dunnington Tobacco Company in Farmville, Virginia. Just two years later, in 1872, Walter joined his father in the business. Through his efforts, the company’s reputation extended worldwide, securing clients from as far as Italy, Austria, and even Norway.

Initially specializing in dark-fired tobacco, the company later shifted to bright leaf, aligning with the booming cigarette manufacturing industry in Virginia and North Carolina towards the late 19th century. Norway emerged as a key market, with a staggering 30 train cars laden with tobacco departing from Farmville in 1902, bound for Norwegian shores via the Norfolk and Western Railway.

Operating on a vast expanse of over 1,100 acres, known as Poplar Hill Farm, the company thrived. One of its original warehouses, situated on the Appomattox River at Mill and First Street, now houses Charley’s Waterfront Cafe and a section of the Green Front Furniture Company.

But tobacco wasn’t Walter’s sole venture; he also ventured into banking, becoming associated with Farmville’s First National Bank. Additionally, he co-owned the Virginia State Fertilizer Company with Walter H. Robertson. Engaging in community affairs, Walter served as a trustee for Hampden-Sydney College in 1897, the same year he and his wife moved into their palatial estate.

Walter Grey Dunnington passed away on August 1, 1922, leaving behind his wife, India, and son, also named Walter. India remained in the mansion for another 40 years after Walter’s passing, living until the remarkable age of 103. Witnessing the transition from horse-drawn carriages to automobiles and the dawn of technological marvels like the light bulb and television, India’s life was a testament to the rapid pace of progress. She and Walter are interred at Westview Cemetery in Farmville, while their son rests in Southampton Cemetery in Suffolk County, New York.

Following India’s passing, the Dunnington Mansion remained occupied and well-maintained, although details about its occupants between 1960 and 1998 are scarce.

At one juncture, there were plans by the golf course to restore the historic mansion for potential use as a venue for guests and events. Regrettably, these aspirations were dashed due to financial constraints brought on by economic downturns.

Among those with memories tied to the property is local resident Virginia Dowler Dickhoff, whose childhood was intertwined with the old Dunnington estate. Her father, hailing from Canada, played a role in tending to the farm and nurturing the field crops. This insight was gleaned from online sources, shared by a former neighbor of Virginia’s. Sadly, Virginia passed away on January 15, 2020.

The mansion was put up for auction through a sealed bid process in October. The deadline for bids on the 361-acre parcel of land, encompassing the mansion, was set for 3 pm on Wednesday, October 7, 2020.